Funny Expressions Bees Knees Cats Wiskers

Bee's Knees and Cat's Whiskers

Just the other day, a writer for Men's Health requested an interview with me about the origin and evolution of the jock strap, supporter, and cup — which prompted my recall of the venerable Jacques Strop, a character in Robert Macaire, a once-famous play of the 1830s. I had little else to offer the interviewer, but this essay, penned for The Woodstock Times a decade ago, leapt to mind. I think it's still pretty good (probably I should say swell); maybe you will too.

Miss Doherty's assignment to her English section of sophomores at Richmond Hill High School was to write a single-page essay on "My Favorite Books." My response was to award the palm to Heinrich Harrer's Seven Years in Tibet, the book I had most recently read; mild approbation to Conan Doyle's Hound of the Baskervilles and mysteries in general; and short shrift to the entire genre of military books, which I said I just "couldn't stand." Miss Doherty indulged my opinions and kindly graded the essay at 90, but noted in the margin that my chatty remark that had meant to tar-brush everyone from Martial to Churchill was "colloq" [colloquial] and thus deficient. By way of explanation after returning the paper to me, she added that good writing was "elevated speech."

For decades I had displayed that naïve and frankly not so hot ("colloq") essay in a frame on the wall of my study, to chasten me and to hearten others who might pause to read it. Today it resides in a box in storage, and I have come to like Miss Doherty less well than I did when I was her pupil in 1960. Only in recent years have I realized the lasting impact of her offhand observation that good writing is somehow more formal, more structured, more dignified than good talk. I became an English major in college and wrote stiff and stuffy if well received papers. I became a professional writer of sports-history books, differing from my peers in that my prose seemed generally professorial and chilly where theirs was often imprecise yet energetic.

Well, folks, Miss Doherty was wrong — it turns out that the best writing is that closest to the best talk, if not the same damn thing. I could have learned this from Mark Twain, from Joseph Mitchell, from H.L. Mencken — from Walt Whitman, above all! — and countless others who often turned fancy phrases but never abandoned their unique voices. But for the longest time I somehow thought that it was a delicious subtlety for an author to throw his voice across the room like a ventriloquist. When I would toss a colloquial or slang term into an archly constructed sentence my purpose was to jar, to amuse, and then to return, invigorated, to an expository manner. I knew I was injecting pop into otherwise staid sentences but I didn't wonder why it was that I could rely upon that outcome, or what particular powers these "low-brow" words had.

Lately I have begun to come around, and it is my prolific email habit that I have to thank. Writing speedily and often thoughtlessly, I have neatly bypassed Miss Doherty's censors (and more importantly my own) and defaulted to my own voice, my own ear, and my own love of words once all the rage but now quaint — swell (first appearance in print 1897), crummy (1859), nifty (1868), jerk (1935), groovy (1941). I had always been archaeologically inclined, ever since boyhood, wondering how things began, how they migrated from there to here, why they flourished or why they disappeared. Whether my curiosity attached to rock 'n' roll and advanced backwards to the blues and jazz and West African music, or to baseball and its bat-and-ball variants going back to the Egypt of the pharaohs, or to the special argot of all sport with its capacity to originate terms that come into common parlance or to purloin terms from other fields and redefine them, my path was always the same: learn the story behind the thing at hand and use that as a lens with which to see and understand both the past and the present.

The power of patois is that it comes from the bottom up, without social sanction, often from special-interest subcultures (surfers, techies, druggies) or ethnic or sexual minorities, and always with a slanting, often humorous, stance toward majority culture. Most of it vanishes rapidly — notably, in our day, once the mass-media gurus get their hands on it ("Here come da Judge!") — indeed, so rapidly that even a generation later we are left to wonder what the catch-phrase meant in the first place. The derivation of off-color terminology was particularly amusing to trace when I was a schoolboy, and my enduring interest in such sleuthing is one of the many ways in which I have proudly arrested my development. (When I wrote a column called "The Magic Glute" a few weeks back I had a long and, to me at least, fascinating explanation for how one's bottom came to be termed an ass; however, I couldn't wedge it into that story any more than I can into this.)

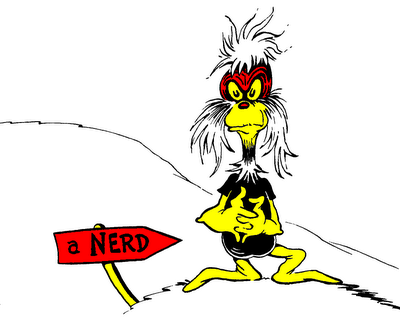

Other men may lust after Boxters, iPods, and trophy wives; I have my microfilm reader, my Harry Potter magnifying glass, and my compact edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. For me adventure is at all times but a step away. Although I am a nerd (first appearance in print 1957; probable origin a character in a Dr. Seuss book of seven years earlier, If I Ran the Zoo), I am not singular in such pursuits. I have a good many friends who would proudly describe themselves as geeks (1875!). One, Skip McAfee of Virginia, engaged in a spirited debate over the meaning of the baseball phrase "Out of Left Field," answering a query by Professor Bill Rubinstein of Australia by refuting certain explanations offered by amateur philologist and professional word maven ("colloq") William Safire of the New York Times. Another, George A. Thompson, contributed to a thread I had started on a bulletin board for aficionados of nineteenth century baseball about the nautical origins of such baseball terms as "skipper" (captain, later manager, of a nine), "on deck" (next batter), "in the hold" (next batter after that), "around the horn" (a double play initiated by the third baseman, then on to the second baseman, and finally the first baseman, but earlier derived from ships sailing around Cape Horn to Western ports, and earlier still, from the Dutch city of Hoorn), and "skyscraper" (an early baseball term for a pop fly, but even earlier, in 1794, a triangular topsail also called a moon-raker).

Priscilla Astifan of Rochester wrote to me about these matters nautical, saying, "it's fascinating the way old references prevail even when the associations that initiated them are long gone," a fine observation to which I replied: "I love these archaisms or vestiges, too. It's downright hilarious that sportswriters today will write 'Martinez was knocked out of the box' or 'Boston notched three runs in its half of the inning.' Not a mother's son of them seems aware that we haven't had a pitcher's box since 1892 and we haven't counted runs by scoring notches into a stick since the 1840s."

Peter Morris convinced me that his explanation for the derivation of the baseball word "fan" was correct: that the term was originally used in derision, as an insiders' (players, managers, owners) dismissal of outsider wannabes . As I wrote to him, "The idea of ceaseless tongue-flapping being a metaphorical fan seems right, and the 'controversy' of 'fanatic' vs. 'fancy' [as the source of 'fan'] seems contrived and incongruent with the class character of the baseball set…. Imagine looking upon a crowd of several thousand people all fanning themselves — might you not refer to the congregants themselves as fans, just as the original operators of typewriters were themselves named for their instruments? (Only later were they called typists.) Or maybe the name comes from the incessant chatter and debate by which true baseball devotees are known."

In a similar example of synecdoche, in which the name of the part is transferred to the whole, today a visibly athletic male (or oddly and increasingly, and no longer disparagingly, a female) is termed a "jock." This term derives not from a horse jockey but from the jock strap worn to support the male genitalia in active sport. Okay — but where does "jock strap" come from? Not from the racetrack, I suggest, but from Jacques Strop, a supporting character in Robert Macaire, an obscure 1830s play by Benjamin Antier. Ya heard it here first.

Ditto for the true origin of Murderers' Row, a term used to describe the middle of the batting order of the 1927 New York Yankees. While the usual etymology for this term is plausible — that it derives from a row of cells in New York's Tombs prison reserved for the most dastardly of criminals — Murderers' Row was an actual alley in Manhattan long before the Civil War, starting where Watts Street ended at Sullivan Street, midway along the block between Grand and Broome Streets. Checking an 1827 listing of street names, I found that such location matched a street name: Otter's Alley, which ran from Thompson to Sullivan Streets between Broome and Grand Streets.

Other sports terms besides those in baseball hold wonderful trace memories of their early days. The football field is called a gridiron because a hundred years ago it was marked not only by horizontal lines representing each five-yard distance, but also vertical lines five yards apart. And to this day basketball players are sometimes called, notably by headline writers short of character space, "cagers." Why? Because the game was originally played within a metal cage designed to keep the ball out of the stands and the fans in them. Given the [then recent; 2004] fracas in Detroit, a cage seems an idea whose time has come back.

There are peculiar antique terms in all of our sports that many will struggle to explain. Mention "mashie niblick" and you'll always get a perplexed laugh. But in the days when few golfers carried what we could call a full complement of clubs, the number of irons was reduced. A mashie equated to a five iron and a niblick to a nine iron (the club whose face slanted more than any club except a wedge). Those not carrying both clubs might opt for a mashie niblick, which would equate to a seven iron.

I could go on, but space constraints begin to pinch [oh, for the newsprint days of yore!]. John Ayto, editor of The Oxford Dictionary of Slang, writes in the preface to that volume: "From the earliest exposés of underworld cant from writers such as John Awdelay and Thomas Harman in the sixteenth century, through Francis Grose's pioneering Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785), J. S. Farmer and W. E. Henley's seven-volume Slang and Its Analogues (1890–1904), and Eric Partridge's influential Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (1936), to Jonathan Lighter's Historical Dictionary of American Slang (1994 — ), the development of colloquial English vocabulary has been voluminously and enthusiastically documented."

SIDEBAR: A Selection from The Oxford Dictionary of Slang

Here, not voluminously but certainly enthusiastically, are some words and phrases I particularly like, along with the often surprising date of their first appearance in print using their current meanings. Almost always the first appearance of a slang word in print does not mark the beginning of its usage, and with almost equal certainty, the first appearance is substantially earlier than one might have imagined.

Bees Knees (1923)

Cats Pajamas, Cat's Meow, Cat's Whiskers (1921–23)

23 Skidoo (1926, origin unknown)

86 (1936; the folks at Chumley's Restaurant at 86 Bedford Street in NYC will tell you different)

Makin' Whoopee (1928)

Rave or Rave-Up (1960)

Cool (1933)

Chill Out (1980)

The Blues (1741 — derives from "blue devils")

Neat (1934)

Nifty (1868)

Spiffy (1853)

Natty (1785)

Snappy (1881)

Hip (1951)

Hep (1957; surely the editors have this pegged too late)

Bodacious (1843)

Together (1968)

Happening (1977)

Snazzy (1932)

Sharp (1940)

Ducky (1897)

Unreal (1965)

Hot (sexual desire, 1500; erotic, 1892; skillful, 1914; fashionable, 1908)

Groovy (1941)

Fab (1957)

Gear (1951)

Swinging (1958 as "trendy")

In (1960)

Trendy (1962)

Awesome (1975)

Def (1979)

Killer (1979)

Rad (1982)

Radical (1971)

Hipster (1941)

Hippie (1953)

Cat (1920)

Chick (1899)

Fox (1961, back formation from foxy of 1895)

Dude (1883, but in sense of "fancy dan")

Lousy (1596 … yes)

Crummy (1859; from crumb as body louse)

Schlock (1915)

N.B.G. (no bloody good, 1903; today often seen as N.F.G.)

Turkey (as stinker, 1927)

Icky (1939)

Gross (1958)

Grody (1965; from grotesque)

Jerk (1935)

Geek (1875)

Wimp (1920)

Nerd (1957)

Bug (1841)

Stoked (1963, surfing term)

Kook (1951, surfing derivation)

Outasight (1893)

Bad (as good) 1897

Swell (1897)

Wicked (as good) 1920

Far Out (1954)

Wannabe (1988)

mccaryraidaured74.blogspot.com

Source: https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/bees-knees-and-cat-s-whiskers-cdece5ed166b

0 Response to "Funny Expressions Bees Knees Cats Wiskers"

Post a Comment