what happened to most of the workmen who built the terracotta army and tomb

Army of the First Emperor of Qin in pits next to his burial mound, Lintong, People's republic of china, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: scottgunn, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Background: the first emperor of Prc

The beginning emperor of China was Qin Shi Huangdi. First, he became king of the Qin (pronounced "Chin") land at the historic period of thirteen. Eventually he defeated the rulers of all the competing Chinese states, unifying China and declaring himself "Commencement Emperor of the Qin Dynasty" (Qin Shi Huangdi). He began the construction of his vast tomb as soon as he took the throne, and it took 38 years to finish, even with a reported 700,000 convicts laboring for the last thirteen years of construction. These smashing numbers are, themselves, displays of the tremendous ability of the emperor, and the work clearly bears the imprint of their astounding labors.

As emperor, he was repressive —banning and burning Confucian books and executing the scholars who wrote and studied them. Not surprisingly there were at least ii attempts to assassinate him.

Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi today, (photo: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Visual elements

When the tomb was completed, it was covered in grass and copse, so that information technology would appear like a natural part of the landscape.

Today, from the outside, Qin Shi Huangdi'due south burying mound looks like a colina. This explains how the huge tomb could have remained subconscious until 1974 when rural villagers accidentally discovered it while earthworks a well. It blended into its surroundings, looking similar a foothill of the Li Mountains.

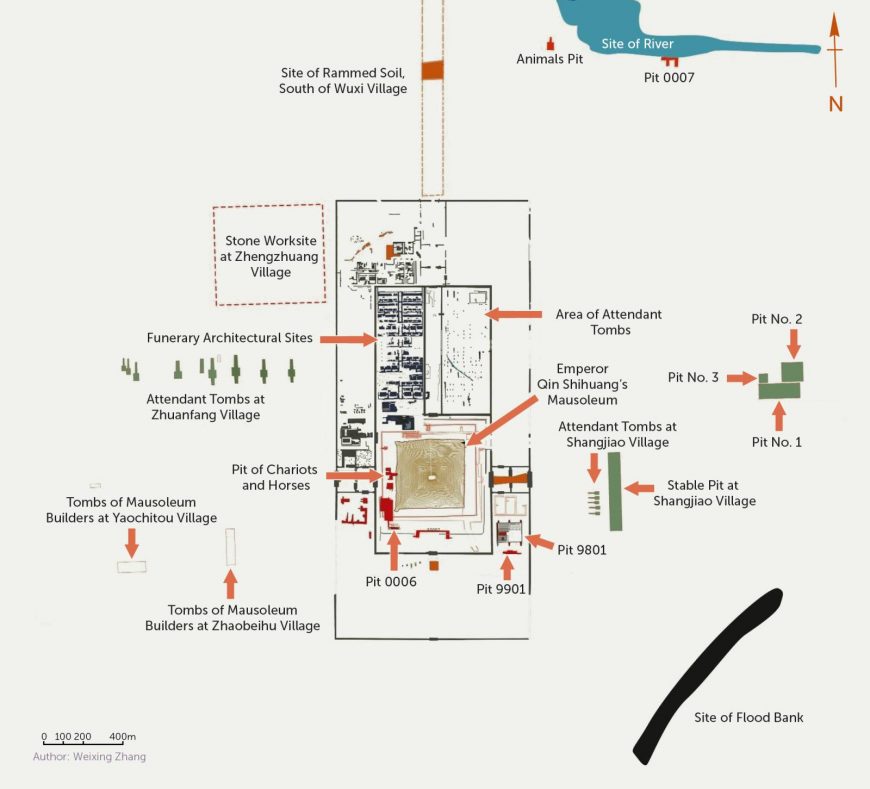

Plan of the tomb complex, Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi (diagram Weixing Zhang)

Every bit the plan of the tomb circuitous shows, the tomb itself was surrounded by a big number of other burials, including three pits containing warriors made from terracotta (which are known today as the "Terracotta Army") At that place was likewise a pit filled with the remains of exotic animals, and the graves of followers executed at the time of the burial.

So far, approximately vii,000 figures made from terracotta and 100 wooden chariots have been discovered in Pits 1, 2 and 3.

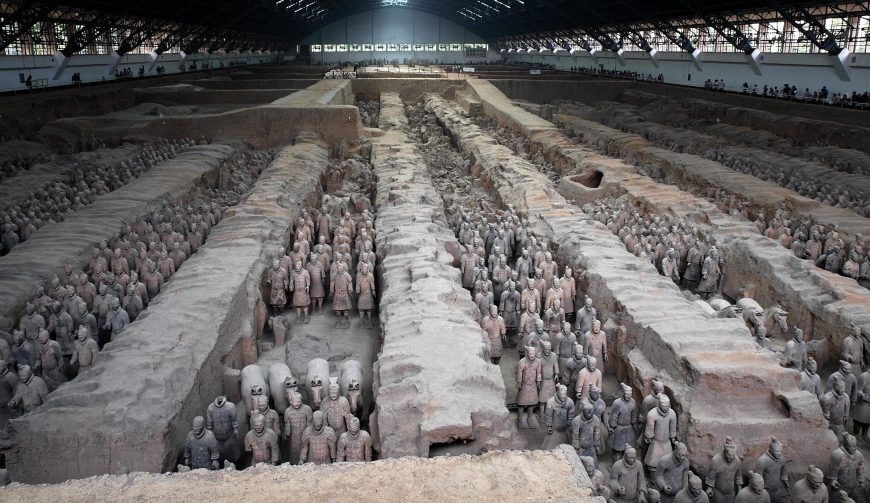

Pit 1, Army of the First Emperor, Qin dynasty, Lintong, China, c. 210 B.C.Due east., painted terracotta (photo: mararie, CC By-SA 2.0,

When we look at the vast rows of the vi,000 soldiers of the ground forces in Pit i (the largest still establish) we see a view that no ane had seen for more than two thousand years — from the time that the tombs were sealed until the excavations of the 1970s. The figures were set into paved channels of earth, reinforced with wooden planks and then cached.

The soldiers are arranged in battle formation, with a vanguard of archers surrounding the bulk of the army. The easily of the archers are now empty, but they originally held wooden bows, of which some traces survive. These wooden bows, forth with statuary weapons held past other soldiers, would have given the soldiers a more naturalistic appearance.

Front and back view of Kneeling Archer, Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi

Blueprint and repetition

As a whole, the layout and design of the army emphasizes pattern and repetition. The soldiers are all of very like size — slightly larger than life-— and are standing in repeated poses. They are arranged in consistent rows, which establishes a very regular pattern. Information technology also creates a sense of unity, which is an ideal generally sought past real armies. These soldiers are clearly, through their unified appearances, collectively working to express, enforce and protect the power of the emperor, fifty-fifty every bit he lies in his grave. In that location is, though, variety throughout the regular army, enlivening the whole with small, humanizing differences in features and costume.

Scale

The scale of the project is hard to embrace. This is not a token set of guards around the majestic tomb, but a complete army, from foot soldiers and cavalrymen to generals. To become a sense of these figures, we will look start at an archer from Pit 2. The archer wears a long robe and armor over his torso and shoulders and kneels on his right knee. He originally held a bronze crossbow, a weapon that shot heavier arrows faster and farther than bows.

His armor is quite detailed. The immensity of the labor required to produce the thousands of figures is stressed by viewing the figure from the back, revealing the attention paid fifty-fifty to the sole of his shoe. It bears three different patterns in the tread, to differentiate heel, heart and toe. The intendance taken over such a minor item emphasizes the power of the patron, and the vastness of his wealth.

Nonetheless, while in that location is great attending to detail, which suggests the individuality of the figures, in that location are also techniques used to grant the whole composition its consistent and impressive unity. The most obvious method used to create a sense of unity is the depiction of their armor: since they are an ground forces, they are dressed in very consistent uniforms. There are, though, subtler techniques used to suggest that the figures are not actually individual portraits but slightly differentiated versions of a generalized, idealized soldier. The folds of the archer's clothing, for example, are stylized: we know that the heavy cuts into the surface of the terracotta stand for folds in heavy cloth, only they do and so in a generalized fashion, rather than seeming like each was carefully copied from reality.

Individualized but abstracted and idealized

The figure'due south confront is too at in one case individualized and slightly bathetic. Its sense of individuality does not come from intense verism, from the rendering of every contraction and imperfection, just from the lively and alert expression. All of the features are smoothed out, fabricated angular. Some of the figures bear bushy moustaches and beards or thick eyebrows, but this figure's features are all more minimally presented. The halves of his moustache are apartment planes, and his eyebrows are smooth ridges.

All of the artist's efforts here seem to exist focused on his watchful state. The effigy, like all of the thousands at the site, is idealized. The archer appears to be youthful and stiff. His face is highly symmetrical, though this is humanized by his off-center acme-knot of pilus. He, like all those around him, is an ideal soldier to serve in the emperor'southward imposing army.

Chariots

Equally impressive are the corking chariots, including the war chariot. These were found but exterior the actual burial of Qin Shi Huangdi (which remains unexcavated at this time). Two statuary chariots were found, one considered a state of war chariot and the other a peace chariot. Both chariots were establish in fragments just have been restored. They are about half life-size, and intricately designed. The war chariot contains golden and silver embellishments on the canopy pole and the horses' bridles, as well as other parts of their tack.

War Chariot, Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, c. 210 B.C.East. (photo: Tiffany, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The horses are depicted in much the same fashion as the terracotta figures, with a frail rest between naturalism and stylization. Their heads and bodies are somewhat generalized, and so that we practise non see veins or tendons standing out below the hibernate, for example, and yet they are yet quite lively. Their ears are perked up as if with attention, their heads tossing as they bite their bits. They were originally painted white, with red tongues, which would have granted them an even more lively appearance.

The horses, like the soldiers, are each individualized, and yet clearly all part of a cohesive team. They are all of the aforementioned size, and wear similar gear, but they differ in subtleties of the nostrils and optics, for example. A crossbow hangs within piece of cake achieve of the driver, elaborately decorated with patterns. A quiver containing 54 bronze arrows of ii different types — diamond-shaped and flat tipped — was found hanging from the within of the chariot'south rail. Once the emperor died and his dynasty was quickly disintegrating, mobs plundered the tomb and took the weapons because they could be used.

Cultural context

The burial of Qin Shi Huangdi reflects the worldly ability of the emperor. In ancient China, very elaborate burials were standard features of imperial courtroom practice, and were copied by bottom members of the elite, besides. In the earlier Shang Dynasty (c. sixteenth-eleventh century B.C.E.), rulers were cached with lavish possessions (as well equally with their servants — human sacrifices were besides mutual in the Shang Dynasty, and connected through successive periods).

By the time that Qin Shi Huangdi commissioned his elaborate tomb, these practices were already aboriginal, and set the precedent for his ritual specialists to follow. Sima Qian's Shiji (Historical Records) provides an account of the tomb (Sima Qian is considered the get-go major historian of People's republic of china; he wrote during the Han Dynasty that succeeded the Qin). His description attests to the continued practice of human sacrifices, as well as the to great measures taken to secure the tomb against raiders seeking its riches.

He tells us:

The tomb vault was dug through 3 underground streams and the coffins were cast in copper. Palaces were built within the burial mound and the burying chamber itself was a rich repository full of precious and rare treasures. Artisans were commanded to contrive gadgets decision-making subconscious arrows so that if tomb robbers approached they would be bound to touch the gadgets and then trigger the arrows. On the floor of the vault mercury representing the rivers and seas was kept flowing by mechanical devices. The dome of the vault was busy with the sun, moon and stars, and the ground depicted the nine regions and 5 mountains of China. … At the entombment the 2nd Emperor decreed that it was not plumbing fixtures that the childless concubines of the First Emperor should be allowed to leave the imperial palace and should all be buried with the Emperor. Thus the number of those who died was very great.As quoted in Zhang Wenli, The Qin Terra cotta Army: Treasures of Lintong (London: Scala Books, 1996),

xiv-sixteen.

Like near imperial burials in People's republic of china, Qin Shi Huangdi'southward burial chamber remains sealed, and so this early business relationship of its vaults and surroundings has not yet been confirmed (though there are heavy concentrations of mercury in the soil effectually it, suggesting at least some accurateness).

Only why would an emperor wish to be buried with a terracotta army, with statuary chariots and teams of horses, and even with his concubines?

In ancient China, decease was seen not equally the complete end to an private but rather, a new stage in life. Therefore, the army was intended not only to demonstrate the emperor'due south ability in this life, simply also to extend that aforementioned power into the world of the dead.

Admittedly biased Confucian historians of later dynasties draw Qin Shi Huangdi as paranoid, though the ii documented attempts on his life suggest that some fearfulness would not take been irrational. Desiring to preserve his power eternally, he had the ideal army synthetic, and placed to the e of his tomb — the management of his enemies in life.

This massive projection should be seen in the context of Qin Shi Huangdi's other efforts, including the first of the Great Wall of China, built to keep out northern invaders in the earth of the living. The starting time emperor gained unified command over Mainland china through military force, censorship of information and ideas, and a stiff defense confronting outside forces. Having accomplished this, he then worked to ensure that he would continue to concur such worldly power — even later his death.

Additional resource

Red china's Terracotta Warriors: The First Emperor's Legacy exhibition at the Asian Art Museum (2013)

mccaryraidaured74.blogspot.com

Source: https://smarthistory.org/terracotta-army-emperor-qin-shi-huangdi/

0 Response to "what happened to most of the workmen who built the terracotta army and tomb"

Post a Comment